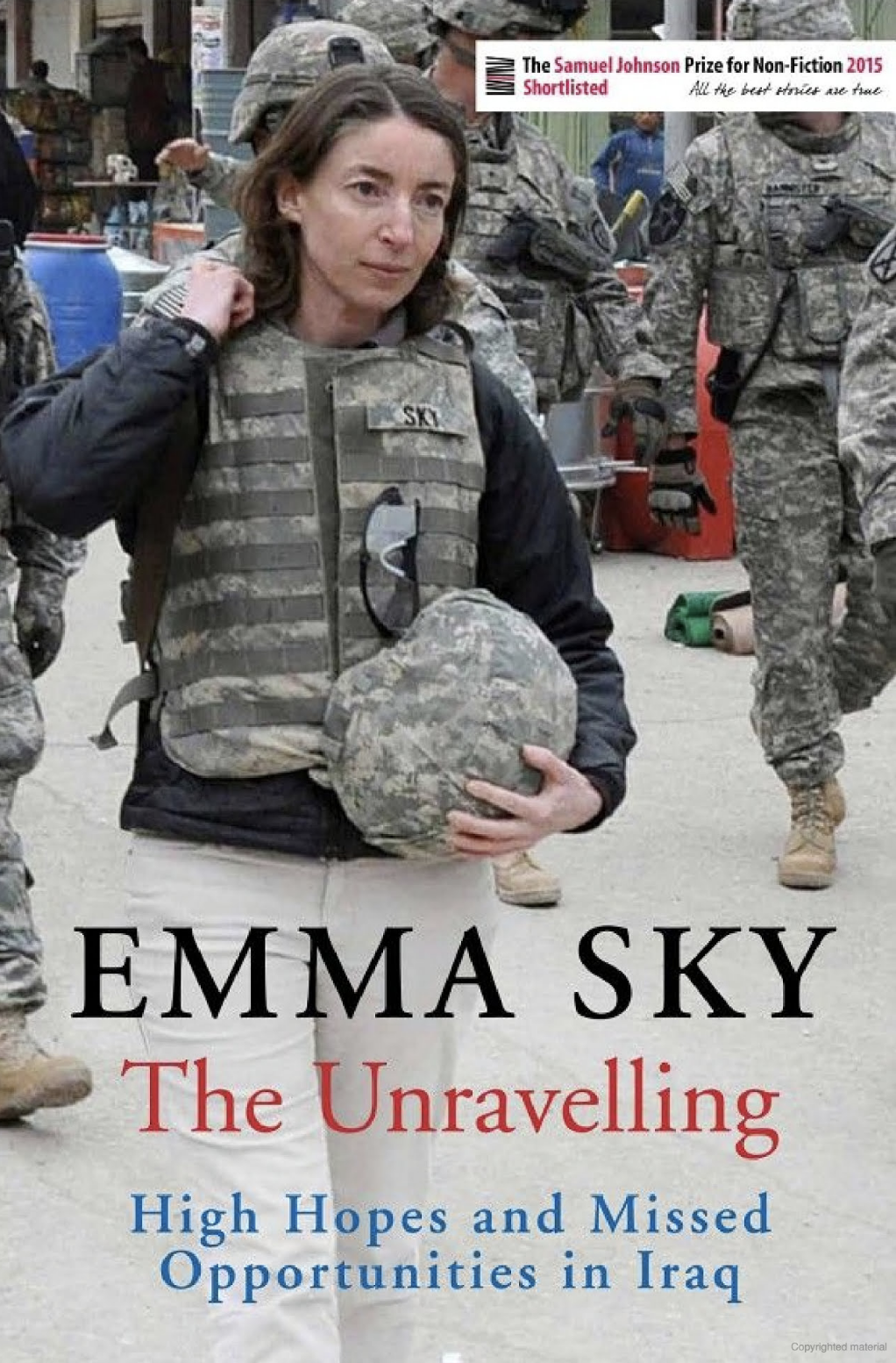

I have an almost instinctively antipathetic feeling towards Emma Sky’s The Unravelling, which resurfaces every so often throughout her book. Oddly, the more I read, the more I was sure she would have felt something similar had she been merely reading it as opposed to being the book’s narrator. Ultimately, however, The Unravelling is a must-read for anyone interested in the 2003 invasion of Iraq, and its catastrophic consequences.

In the lead up to the war, Emma Sky knew her own mind, and it was determinedly against the US-led invasion. She claims to come from an unremarkable, albeit broken, home, though her schooling (her mother was a matron at a private school, where she became a pupil) suggests different. Compared to run-of-the-mill working-class kids in the UK, this alone meant she was in a different league in life opportunity terms.

It helps if such an opportunity comes with intelligence, and she won a place at Oxford, where she further developed her passion for the Middle East. She worked for NGOs and the British Council there, promoting peace between the Palestinians and Israelis.

-

October 2025

- Oct 16, 2025 New study reveals Munich travel habits Oct 16, 2025

-

August 2023

- Aug 29, 2023 Argentina's Andes: beauty and tranquility Aug 29, 2023

-

January 2020

- Jan 8, 2020 Surprised CSU grassroots rejected a Muslim? Jan 8, 2020

-

December 2019

- Dec 13, 2019 It’s not just MPs who you’ve lost Dec 13, 2019

-

July 2019

- Jul 4, 2019 Robert Andreasch, worthy winner of Munich journalism award Jul 4, 2019

- Jul 1, 2019 Munich police raid on refugee shelter leaves mother with broken arm and son arrested Jul 1, 2019

-

May 2019

- May 5, 2019 New Pinakothek, exhibition: Die Neue Heimat (1950-1982), A Public Housing Corporation and Its Building May 5, 2019

- May 1, 2019 Spotlight magazine - Munich’s Brits: a sporting community May 1, 2019

-

April 2019

- Apr 17, 2019 Paris and Taq Kasra, Baghdad Apr 17, 2019

- Apr 11, 2019 Denmark Apr 11, 2019

-

March 2019

- Mar 8, 2019 Passport decision time Mar 8, 2019

-

February 2019

- Feb 24, 2019 Business Spotlight: Brexit Britain Feb 24, 2019

- Feb 14, 2019 Munich's Fridays For Future Feb 14, 2019

-

January 2019

- Jan 28, 2019 Book Review: The Unravelling. High Hopes and Missed Opportunities in Iraq Jan 28, 2019

- Jan 15, 2019 Book review - John Robertson, Iraq. A History Jan 15, 2019

- Jan 1, 2019 Poverty Safari, Darren McGarvey Jan 1, 2019

-

December 2018

- Dec 28, 2018 Iraqi artist recreates 3D ancient cities Dec 28, 2018

-

November 2018

- Nov 28, 2018 Ireland: Waterford and the King of the Vikings Nov 28, 2018

- Nov 27, 2018 Spotlight: Pakistan Nov 27, 2018

- Nov 12, 2018 Business Spotlight: Israel Nov 12, 2018

- Nov 10, 2018 Business Spotlight magazine: South Korea Nov 10, 2018

- Nov 2, 2018 Thousands of dead fish ... the rivers of Babylon Nov 2, 2018

- Nov 1, 2018 Lacrosse interview – German and US players in Munich Nov 1, 2018

-

October 2018

- Oct 31, 2018 Book review: Alan Rusbridger, Breaking News. The Remaking of Journalism and Why It Matters Now Oct 31, 2018

- Oct 26, 2018 Food: Sababa, Munich's best falafal restaurant Oct 26, 2018

- Oct 19, 2018 CSU loss is a Green gain Oct 19, 2018

- Oct 18, 2018 Gozo's Ta Tumasa & hints of the Middle East Oct 18, 2018

- Oct 18, 2018 The Price of Plastic - For One Turtle Oct 18, 2018

- Oct 14, 2018 Visit Malta, stay on Gozo Oct 14, 2018

She volunteered for three months to help in the aftermath of the 2003 invasion, and – reflecting the Allied lack of a robust plan for after the defeat of Saddam Hussein – quickly (and still, for me, inexplicably) became the de-facto governor of the province of Kirkuk. Almost comically, as she told the UK’s post-war Iraq Inquiry, she received no prior instructions as to what her job would be, never mind being named as a governor. She went on to become the political advisor to the US military, notably Colonel William Mayville and General Ray Odierno, both of whom come out of Sky’s book vey well.

As well as providing great first-hand contextualisation of various ethnic, religious, geographical and personal disputes across the country, she does not exculpate the US for its role in the ‘unravelling’ – even if she might frustrate some in her refusal to be more brutal in her criticism. She chides Joe Biden and President Obama for their support of former prime minister Nuri al-Mailiki, in the face of clear evidence that he was becoming increasingly authoritarian and factional, and that a civil war might result.

Sky was right in opposing the war in the first place because she had an inkling of what might come, and she was right in her reasons for opposing Maliki. And though it is tempting to damn her for being there, for her claim to have played a role on the ground in offsetting the worst instincts of the occupiers, it’s clear that she genuinely believed in what she was doing.

At the heart of The Unravelling is Sky’s desire to engender a better understanding between different sections of Iraqi society, and between Iraqis and the US military. And though it hardly makes my scepticism of the book completely disappear, this, alongside the fact it’s a compelling read, goes some way to dampening it.